Presented at the School of Visual Arts Symposium on the Sixties

Recollections of the Sixties

Camillo Mac Bica

Caught within the frenzy of trying to organize this symposium, it wasn’t until just the other day, when I sat down to think about what I was going to talk about this evening, that I realized I had assigned myself the task of presenting a coherent, interesting, and insightful discussion of not only the Vietnam War but of the anti-war movement as well, all in about 30 minutes. Clearly, I had lost my perspective on reality and wondered, at that point, whether the sex, drugs, and rock and roll of the Sixties hadn’t caught up with me at last.

Caught within the frenzy of trying to organize this symposium, it wasn’t until just the other day, when I sat down to think about what I was going to talk about this evening, that I realized I had assigned myself the task of presenting a coherent, interesting, and insightful discussion of not only the Vietnam War but of the anti-war movement as well, all in about 30 minutes. Clearly, I had lost my perspective on reality and wondered, at that point, whether the sex, drugs, and rock and roll of the Sixties hadn’t caught up with me at last.

I have spent most of my adult life maneuvering back and forth between two very different worlds. That is, the world of a Vietnam veteran striving to come to grips with the experience of war, and that of a philosopher trying to unpack and understand the experience theoretically.Since a twenty to thirty minute discussion would hardly scratch the surface of detailing the history and complex nature of America’s involvement in Vietnam and of the civil unrest it engendered, I decided that, perhaps, my time would be most productively spent by sharing with you, this evening, some observations I have made from the combined perspective of a veteran and a philosopher. I will begin with some commentary about my life and personal experiences in Vietnam and conclude with a philosophical discussion of how I, and many others, were and continue to be, manipulated to fight, kill, and die, in senseless, immoral wars.

I have spent most of my adult life maneuvering back and forth between two very different worlds. That is, the world of a Vietnam veteran striving to come to grips with the experience of war, and that of a philosopher trying to unpack and understand the experience theoretically.Since a twenty to thirty minute discussion would hardly scratch the surface of detailing the history and complex nature of America’s involvement in Vietnam and of the civil unrest it engendered, I decided that, perhaps, my time would be most productively spent by sharing with you, this evening, some observations I have made from the combined perspective of a veteran and a philosopher. I will begin with some commentary about my life and personal experiences in Vietnam and conclude with a philosophical discussion of how I, and many others, were and continue to be, manipulated to fight, kill, and die, in senseless, immoral wars.

I was raised to be respectful of god and of Country influenced by the devout patriotism of my immigrant parents grateful to be living in this land of freedom and opportunity. Further conditioned by an austere Catholic School education and a steady diet of John Wayne movies, I took very seriously John F. Kennedy’s admonishment to “Ask not what your Country can do for you, ask what you can do for your Country.” In fact, though I am embarrassed to admit it today, I actually remember saying on a few occasions when pressed, “My Country right or wrong,” as though blind patriotism and obedience constituted rational explanation and moral justification for our nation’s actions.

I was raised to be respectful of god and of Country influenced by the devout patriotism of my immigrant parents grateful to be living in this land of freedom and opportunity. Further conditioned by an austere Catholic School education and a steady diet of John Wayne movies, I took very seriously John F. Kennedy’s admonishment to “Ask not what your Country can do for you, ask what you can do for your Country.” In fact, though I am embarrassed to admit it today, I actually remember saying on a few occasions when pressed, “My Country right or wrong,” as though blind patriotism and obedience constituted rational explanation and moral justification for our nation’s actions.

Before my father was even a citizen // he was fighting in WWII. My uncles fought in the Korea. Mine was a family that not only enjoyed the benefits of America but recognized and accepted their obligation to give back as well. So I guess it was inevitable, that should a situation of peril arise I too must step up to the challenge. So when it became clear, or ast least, I became convinced, that the Communist threat was real and immanent, I enlisted in the Marine Corps Officer Training program. After spending some 12 weeks in boot camp and upon graduation from college, I was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the greatest fighting force the world has ever known. Or so I believed. I believed because I accepted the mythology, embraced Marine esprit de corps, and was proud to be part of the brotherhood, the warrior elite. I had achieved immortality.

Before my father was even a citizen // he was fighting in WWII. My uncles fought in the Korea. Mine was a family that not only enjoyed the benefits of America but recognized and accepted their obligation to give back as well. So I guess it was inevitable, that should a situation of peril arise I too must step up to the challenge. So when it became clear, or ast least, I became convinced, that the Communist threat was real and immanent, I enlisted in the Marine Corps Officer Training program. After spending some 12 weeks in boot camp and upon graduation from college, I was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the greatest fighting force the world has ever known. Or so I believed. I believed because I accepted the mythology, embraced Marine esprit de corps, and was proud to be part of the brotherhood, the warrior elite. I had achieved immortality.

"I do solemnly swear that I will support and defend

the Constitution of the United States against all enemies,

foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and

allegiance to the same; and that I will obey the orders

of the President of the United States and the orders of

the officers appointed over me, according to regulations

and the Uniform Code of Military Justice. So help me

God. ""

I believed, as well, in our political leaders, that America was a great and moral nation, // that Communism was an absolute evil, and the dominoes were falling, and that it was my job to keep our Country safe and strong. Besides, wasn’t it preferable to fight these Communist devils in some distant land rather than to wait and then to have to fight them on the streets of San Francisco? It wasn’t all xenophobic either as I believed we had an ethical obligation to help those less fortunate - - those unable to enjoy freedom and American style democracy.So I went to Vietnam to defend America // and to ensure the freedom of the Vietnamese people.

I believed, as well, in our political leaders, that America was a great and moral nation, // that Communism was an absolute evil, and the dominoes were falling, and that it was my job to keep our Country safe and strong. Besides, wasn’t it preferable to fight these Communist devils in some distant land rather than to wait and then to have to fight them on the streets of San Francisco? It wasn’t all xenophobic either as I believed we had an ethical obligation to help those less fortunate - - those unable to enjoy freedom and American style democracy.So I went to Vietnam to defend America // and to ensure the freedom of the Vietnamese people.

It was soon after the first mortar attack and my first confrontation with the enemy that I realized that despite our military advantage, weapon superiority, domination of the seas and the skies, America, the most powerful nation in the world, was not in control. One series of fiascos followed another, inevitably resulting in the maiming and deaths of individuals who were closer to me than my brother. Despite the frustration of not being able to strike back decisively - - to get revenge - - for a time at least, the remnants of the myth still lingered. With the Marine Corps Hymn playing in the background of my mind, I persevered, and performed well, like Sgt. Striker charging up Mount Suribachi.

It was soon after the first mortar attack and my first confrontation with the enemy that I realized that despite our military advantage, weapon superiority, domination of the seas and the skies, America, the most powerful nation in the world, was not in control. One series of fiascos followed another, inevitably resulting in the maiming and deaths of individuals who were closer to me than my brother. Despite the frustration of not being able to strike back decisively - - to get revenge - - for a time at least, the remnants of the myth still lingered. With the Marine Corps Hymn playing in the background of my mind, I persevered, and performed well, like Sgt. Striker charging up Mount Suribachi.

But unlike in Striker’s war, people do not die quickly, quietly, gently, and without pain and regret. In truth, most linger, and scream for their mothers like children, first imploring god to keep them alive, then begging for death to end their suffering. Final glances exchanged, their eyes burned deeply into my soul. Faces of the soon to be dead, I’ll remember for the rest of my life.

But unlike in Striker’s war, people do not die quickly, quietly, gently, and without pain and regret. In truth, most linger, and scream for their mothers like children, first imploring god to keep them alive, then begging for death to end their suffering. Final glances exchanged, their eyes burned deeply into my soul. Faces of the soon to be dead, I’ll remember for the rest of my life.

To be sure, no one went to Vietnam to become a murderer. I certainly didn’t. In fact our initial motivation was just the opposite, to save lives. But the ambiguity of counter insurgency/guerilla warfare is clearly a no win situation, what Psychiatrist Jay Lifton referred to as an “atrocity producing situation.” Too many young Americans died trying to distinguish the good guys from the bad ‘’ - - in fact I was no longer sure if there were any good guys at all. Regardless, who can take the chance, " Kill them all and let God sort them out”."

To be sure, no one went to Vietnam to become a murderer. I certainly didn’t. In fact our initial motivation was just the opposite, to save lives. But the ambiguity of counter insurgency/guerilla warfare is clearly a no win situation, what Psychiatrist Jay Lifton referred to as an “atrocity producing situation.” Too many young Americans died trying to distinguish the good guys from the bad ‘’ - - in fact I was no longer sure if there were any good guys at all. Regardless, who can take the chance, " Kill them all and let God sort them out”."

Besides, body count was all anyone really cared about. A war of attrition they called it. So, if they’re dead, then they’re re Atrocity? Who knew from atrocity. Survival became our only motivation and ideology, good intentions, honor and nobility gave way to vengeance, and retribution. General Tecumseh Sherman, in explaining his burning Atlanta during the Civil War had it right, I thought, “War is cruelty,” he argued, “and you cannot refine it.” So talk of right and wrong, of morality and ethics, is irrelevant in this context. War is a wild place a place of predator and prey. “Those who made war necessary,” Sherman continued, “deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out.” The most moral thing one can do in war, it has been said, is to get it over as quickly as possible and restore a situation where morality and ethics apply.

Besides, body count was all anyone really cared about. A war of attrition they called it. So, if they’re dead, then they’re re Atrocity? Who knew from atrocity. Survival became our only motivation and ideology, good intentions, honor and nobility gave way to vengeance, and retribution. General Tecumseh Sherman, in explaining his burning Atlanta during the Civil War had it right, I thought, “War is cruelty,” he argued, “and you cannot refine it.” So talk of right and wrong, of morality and ethics, is irrelevant in this context. War is a wild place a place of predator and prey. “Those who made war necessary,” Sherman continued, “deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out.” The most moral thing one can do in war, it has been said, is to get it over as quickly as possible and restore a situation where morality and ethics apply.

Upon my return to the world, to the United States, I arrived at last at Kennedy airport. During my taxi ride home, as we drove passed Aqueduct racetrack, I remember expressing to the driver my amazement that the track was still open that people were there enjoying the races, their lives going on as usual as though the world wasn’t in turmoil, and people weren’t struggling for their survival, making decisions of life and death, mostly death. Looking back, I realize how foolish my comment must have sounded to the taxi driver. But after having spent 13 months in hell, it was unimaginable to me that those in whose behalf I naively thought I was fighting this war were so detached, indifferent to the life and death struggle I was engaged in just 48 hours before.

Now I may not be typical in this but even early on I never felt animosity for those who protested the war. Or those who dodged the draft. Though there were some notable exceptions, in my experience, most antiwar activists were careful to distinguish the war from the warrior. And though I often hear veteran accounts of their being picketed, spat upon, and called baby killers by protestors, it never happened to me.

Now I may not be typical in this but even early on I never felt animosity for those who protested the war. Or those who dodged the draft. Though there were some notable exceptions, in my experience, most antiwar activists were careful to distinguish the war from the warrior. And though I often hear veteran accounts of their being picketed, spat upon, and called baby killers by protestors, it never happened to me.

In fact, as the futility of the enterprise became apparent, it occurred to me as I slogged through the jungles and rice paddies, wet, cold and miserable, that ending the war as quickly as possible was certainly in my interest. And that those who claimed to be supporting the troops, supporting me, were also supporting a war that could very likely end my life. Plus I knew many veterans had become active in the antiwar movement, who, because they understood war, were now trying to stop it. So if the folks at home were truly interested in supporting us, I thought, forget about those yellow ribbons and waving those damn flags. It means nothing. Just get us the hell out of here!!

In fact, as the futility of the enterprise became apparent, it occurred to me as I slogged through the jungles and rice paddies, wet, cold and miserable, that ending the war as quickly as possible was certainly in my interest. And that those who claimed to be supporting the troops, supporting me, were also supporting a war that could very likely end my life. Plus I knew many veterans had become active in the antiwar movement, who, because they understood war, were now trying to stop it. So if the folks at home were truly interested in supporting us, I thought, forget about those yellow ribbons and waving those damn flags. It means nothing. Just get us the hell out of here!!

I’ll tell you who did annoy me, however, and continues to annoy me to this very day. It’s those hypocrites who, while ardently and hawkishly advocating the war in Vietnam, had “other priorities,” or thought themselves too important, or the cause unworthy, or the risks too great, and, through wealth and influence, avoided having to experience war themselves. Today, in positions of power, these chickenhawks continue to rattle their sabers and beat the drums of war while, cavalierly and with clear consciences, sending the sons and daughters of those less fortunate to fight, kill, and to die in another misguided and unnecessary war, this time of their own devise.

I’ll tell you who did annoy me, however, and continues to annoy me to this very day. It’s those hypocrites who, while ardently and hawkishly advocating the war in Vietnam, had “other priorities,” or thought themselves too important, or the cause unworthy, or the risks too great, and, through wealth and influence, avoided having to experience war themselves. Today, in positions of power, these chickenhawks continue to rattle their sabers and beat the drums of war while, cavalierly and with clear consciences, sending the sons and daughters of those less fortunate to fight, kill, and to die in another misguided and unnecessary war, this time of their own devise.

Forty years ago, I had embraced the myth that Vietnam was a noble crusade and we were knights in shining armor struggling heroically and selflessly to defend America from Communism and to ensure freedom and democracy in Vietnam. And when I realized the reality of the enterprise, I felt both the victim and the victimizer, betrayed by the lies and deceit of my political leaders and the betrayer of my integrity and of the values I held so sacred. In the time that remains, I would like to discuss the scope and nature of this myth and how it was and is used today to suppress dissent and misrepresent patriotism as the unquestioning participation in and support for war.

Forty years ago, I had embraced the myth that Vietnam was a noble crusade and we were knights in shining armor struggling heroically and selflessly to defend America from Communism and to ensure freedom and democracy in Vietnam. And when I realized the reality of the enterprise, I felt both the victim and the victimizer, betrayed by the lies and deceit of my political leaders and the betrayer of my integrity and of the values I held so sacred. In the time that remains, I would like to discuss the scope and nature of this myth and how it was and is used today to suppress dissent and misrepresent patriotism as the unquestioning participation in and support for war.

This move to mythologize war is multifaceted and continually being refined and perfected. First, it contrives the illusion that war is necessary to defend America from some absolute evil. Second, it portrays war as antiseptic prohibiting any media reporting that would reveal its inevitable horrors. Third, it appropriates religious rhetoric to depict war as a holy crusade against evil encouraging participation as righteous, glorious, honorable, and heroic. Fourth, it blurs the distinction between the enterprise of war and those human beings who do the fighting, killing, and dying. Fifth, it seeks the silence and compliance of those most likely to realize the deception - - members of the military, veterans, and gold star family members - - by heinously exploiting their pain, suffering, and grief. Finally, it seeks support for the war or at least discourages opposition by preying upon the gratitude, empathy, and guilt of an ill-informed public now convinced that these sacrifices are made in their behalf. Caught within the frenzy of mythological war, we are bewildered and confused into ignoring legal and moral concerns, into rationalizing justification and warrant, and inevitably into celebrating the cause as noble and the sacrifices as necessary. Consequently, we feel the exigency of accepting, though perhaps uneasily, as a patriotic and civic duty, the imperative not to question the justness or necessity of any war we wage, nor to criticize our political leaders, nor to dissent against their warist policies. As a result, we have become a culture characterized by hypocrisy and arrogance abiding by a view of war that is mythological and self-serving.

This move to mythologize war is multifaceted and continually being refined and perfected. First, it contrives the illusion that war is necessary to defend America from some absolute evil. Second, it portrays war as antiseptic prohibiting any media reporting that would reveal its inevitable horrors. Third, it appropriates religious rhetoric to depict war as a holy crusade against evil encouraging participation as righteous, glorious, honorable, and heroic. Fourth, it blurs the distinction between the enterprise of war and those human beings who do the fighting, killing, and dying. Fifth, it seeks the silence and compliance of those most likely to realize the deception - - members of the military, veterans, and gold star family members - - by heinously exploiting their pain, suffering, and grief. Finally, it seeks support for the war or at least discourages opposition by preying upon the gratitude, empathy, and guilt of an ill-informed public now convinced that these sacrifices are made in their behalf. Caught within the frenzy of mythological war, we are bewildered and confused into ignoring legal and moral concerns, into rationalizing justification and warrant, and inevitably into celebrating the cause as noble and the sacrifices as necessary. Consequently, we feel the exigency of accepting, though perhaps uneasily, as a patriotic and civic duty, the imperative not to question the justness or necessity of any war we wage, nor to criticize our political leaders, nor to dissent against their warist policies. As a result, we have become a culture characterized by hypocrisy and arrogance abiding by a view of war that is mythological and self-serving.

Judging by the intensity of the debate over the Vietnam War that plagued much of the 2004 Presidential election, clearly the divisiveness of Vietnam has not been resolved. If anything, it has festered, inflamed by similar concerns and questions concerning the legality, morality, purpose, and necessity of the war in Iraq. I submit that the continued polemic about a war some thirty years gone and the antagonism toward opponents of the Iraq war are symptoms of the public’s bewilderment and confusion regarding the realities of war and a consequence of the myth perpetuated by our political leaders pursuant to their goals of hegemony, neocolonialism, and empire.

Judging by the intensity of the debate over the Vietnam War that plagued much of the 2004 Presidential election, clearly the divisiveness of Vietnam has not been resolved. If anything, it has festered, inflamed by similar concerns and questions concerning the legality, morality, purpose, and necessity of the war in Iraq. I submit that the continued polemic about a war some thirty years gone and the antagonism toward opponents of the Iraq war are symptoms of the public’s bewilderment and confusion regarding the realities of war and a consequence of the myth perpetuated by our political leaders pursuant to their goals of hegemony, neocolonialism, and empire.

To illustrate the sophistication, complexity, and impact of this deception, please consider the admonishment delivered by American Legion National Commander Thomas Cadmus at the veterans organization’s annual convention. Cadmus, in an emotional presentation to his fellow Legionnaires, condemned as unpatriotic, even treasonous, anyone, including veterans and gold star family members, clearly a reference to Cindy Sheehan, who would publicly oppose the war in Iraq. Evoking the specter of Vietnam and of Jane Fonda, Cadmus warned, "We had hoped that the lessons learned from the Vietnam War would be clear to our fellow citizens. Public protests against the war here at home while our young men and women are in harm's way on the other side of the globe only provide aid and comfort to our enemies . . . For many of us, the visions of Jane Fonda glibly spouting anti-American messages with the North Vietnamese and protestors denouncing our own forces four decades ago is forever etched in our memories. We must never let that happen again . . .” Rallying behind their leader, the 4,000 delegates to the convention unanimously passed the following resolution. "The American Legion fully supports the President of the United States, the United States Congress and the men, women and leadership of our armed forces as they are engaged in the global war on terrorism and the troops who are engaged in protecting our values and way of life."

To illustrate the sophistication, complexity, and impact of this deception, please consider the admonishment delivered by American Legion National Commander Thomas Cadmus at the veterans organization’s annual convention. Cadmus, in an emotional presentation to his fellow Legionnaires, condemned as unpatriotic, even treasonous, anyone, including veterans and gold star family members, clearly a reference to Cindy Sheehan, who would publicly oppose the war in Iraq. Evoking the specter of Vietnam and of Jane Fonda, Cadmus warned, "We had hoped that the lessons learned from the Vietnam War would be clear to our fellow citizens. Public protests against the war here at home while our young men and women are in harm's way on the other side of the globe only provide aid and comfort to our enemies . . . For many of us, the visions of Jane Fonda glibly spouting anti-American messages with the North Vietnamese and protestors denouncing our own forces four decades ago is forever etched in our memories. We must never let that happen again . . .” Rallying behind their leader, the 4,000 delegates to the convention unanimously passed the following resolution. "The American Legion fully supports the President of the United States, the United States Congress and the men, women and leadership of our armed forces as they are engaged in the global war on terrorism and the troops who are engaged in protecting our values and way of life."

Cadmus, in his diatribe, clearly illustrates his embracing of the myth and his complicity in misrepresenting patriotism and suppressing dissent. What Cadmus may lack in subtlety, he makes up for in audacity and presumption. Notice first that Cadmus is unconcerned with whether the wars in Vietnam and in Iraq were just or necessary and encourages, in his fellow veterans, and presumably, in the rest of us, a similar indifference to issues of morality and justice. Further, in his view, anti war activists such as Jane Fonda were not exercising their 1st amendment right to speak out against and condemn a war they believed unjust and unnecessary, but, rather, demonstrated their lack of patriotism and hatred of our nation by “spouting anti-American” rhetoric. The protestors, in his view, many of whom believed they were calling attention to a pattern of lies, misinformation, and deception,// were not fulfilling their civic responsibilities, but denouncing the troops. What Cadmus is most concerned with and hopes will never happen again is not an unwinnable, immoral quagmire that consumes tens of thousands of human lives and billions of dollars, but, rather, citizen awareness of the injustice and waste and activism that strives to bring it to an end. Sadly, the crucial lesson Cadmus seems to have learned from the debacle of Vietnam was not that disenfranchised people will endure tremendous sacrifices and struggle heroically and steadfastly against foreign occupiers and aggressors, or that military superiority and advanced weapons’ technology do not guarantee victory, but only that, by actively demanding that our Nation act morally and justly and that our leaders be truthful and forthright with the American people, activists were giving aid, comfort, and presumably, encouragement and hope to our enemies.Further, despite evidence to the contrary, Cadmus describes the war in Iraq as the global war on terrorism and, by implication, the soldiers as sacrificing their lives and mental and physical well-being to protect our values and way of life. He concludes, therefore, that we must don our moral blinders and obediently march off to war. At the very least, we must demonstrate our patriotism and concern for the well being of our troops and our gratitude and appreciation for their sacrifices by avoiding and condemning any public dissent and protest and by supporting the President, the Congress, and thereby, the war.

Cadmus, in his diatribe, clearly illustrates his embracing of the myth and his complicity in misrepresenting patriotism and suppressing dissent. What Cadmus may lack in subtlety, he makes up for in audacity and presumption. Notice first that Cadmus is unconcerned with whether the wars in Vietnam and in Iraq were just or necessary and encourages, in his fellow veterans, and presumably, in the rest of us, a similar indifference to issues of morality and justice. Further, in his view, anti war activists such as Jane Fonda were not exercising their 1st amendment right to speak out against and condemn a war they believed unjust and unnecessary, but, rather, demonstrated their lack of patriotism and hatred of our nation by “spouting anti-American” rhetoric. The protestors, in his view, many of whom believed they were calling attention to a pattern of lies, misinformation, and deception,// were not fulfilling their civic responsibilities, but denouncing the troops. What Cadmus is most concerned with and hopes will never happen again is not an unwinnable, immoral quagmire that consumes tens of thousands of human lives and billions of dollars, but, rather, citizen awareness of the injustice and waste and activism that strives to bring it to an end. Sadly, the crucial lesson Cadmus seems to have learned from the debacle of Vietnam was not that disenfranchised people will endure tremendous sacrifices and struggle heroically and steadfastly against foreign occupiers and aggressors, or that military superiority and advanced weapons’ technology do not guarantee victory, but only that, by actively demanding that our Nation act morally and justly and that our leaders be truthful and forthright with the American people, activists were giving aid, comfort, and presumably, encouragement and hope to our enemies.Further, despite evidence to the contrary, Cadmus describes the war in Iraq as the global war on terrorism and, by implication, the soldiers as sacrificing their lives and mental and physical well-being to protect our values and way of life. He concludes, therefore, that we must don our moral blinders and obediently march off to war. At the very least, we must demonstrate our patriotism and concern for the well being of our troops and our gratitude and appreciation for their sacrifices by avoiding and condemning any public dissent and protest and by supporting the President, the Congress, and thereby, the war.

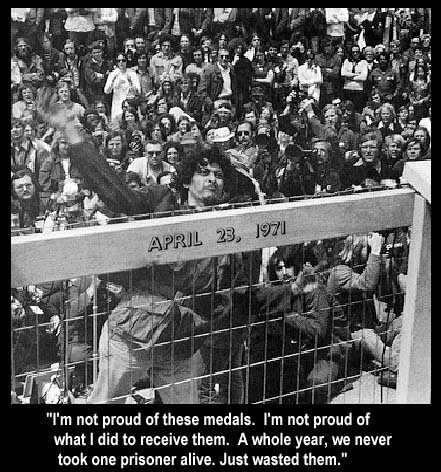

The conclusion to be drawn from this, I think, is not that Mr. Cadmus is conspiring to intentionally confuse and mislead the American people. Rather, what the above makes clear is that the mythologizing of war is so cunning, subtle, compelling, and pervasive that many sincere and rational individuals become unwitting accomplices. The efficiency of the myth and malevolence of the myth makers become apparent when we consider its impact on those rendered most vulnerable by war - - members of the military, veterans, and the families who have lost loved ones. After having experienced the moral ambiguity of guerilla/counterinsurgency warfare, in their efforts to maintain their moral integrity, self-esteem, and to recover from the trauma of war, many veterans, and clearly Mr. Cadmus is one of them, feel impelled to staunchly defend both the Vietnam and Iraq wars. They find comfort in and embrace the myth because of a dread, perhaps unconscious, that unless the war they fought in be remembered as just, and the threat as real, readjustment - - living with the trauma and the memories of the horrors of combat - -// would be unendurable. Consequently, history must be changed to record the Vietnam war as a noble and necessary crusade against the evils of Communism and the invasion of Iraq as a justifiable response to the attacks of 9/11, as integral to the war against global terrorism, and, of late, to the freedom and democracy of the Iraqi people. Accordingly, to preserve their dignity and self-respect within the mythic parameters, vulnerable Vietnam veterans labor to explain and justify America’s first defeat in war. The Vietnam war was lost, they argue, not because they lacked ferocity, bravery, or ability, the noble virtues of the warrior. Rather, victory was stolen from them, by a lack of courage, resolve, and steadfastness of inept public officials, cowardly, self-indulgent college students, and worse, traitoress returning veterans who “betrayed” their comrades by speaking out against the war, revealing the myth, and shamelessly desecrating the warriors’ ethos by publicly discarding their war medals, the icons of mythological heroism.

The conclusion to be drawn from this, I think, is not that Mr. Cadmus is conspiring to intentionally confuse and mislead the American people. Rather, what the above makes clear is that the mythologizing of war is so cunning, subtle, compelling, and pervasive that many sincere and rational individuals become unwitting accomplices. The efficiency of the myth and malevolence of the myth makers become apparent when we consider its impact on those rendered most vulnerable by war - - members of the military, veterans, and the families who have lost loved ones. After having experienced the moral ambiguity of guerilla/counterinsurgency warfare, in their efforts to maintain their moral integrity, self-esteem, and to recover from the trauma of war, many veterans, and clearly Mr. Cadmus is one of them, feel impelled to staunchly defend both the Vietnam and Iraq wars. They find comfort in and embrace the myth because of a dread, perhaps unconscious, that unless the war they fought in be remembered as just, and the threat as real, readjustment - - living with the trauma and the memories of the horrors of combat - -// would be unendurable. Consequently, history must be changed to record the Vietnam war as a noble and necessary crusade against the evils of Communism and the invasion of Iraq as a justifiable response to the attacks of 9/11, as integral to the war against global terrorism, and, of late, to the freedom and democracy of the Iraqi people. Accordingly, to preserve their dignity and self-respect within the mythic parameters, vulnerable Vietnam veterans labor to explain and justify America’s first defeat in war. The Vietnam war was lost, they argue, not because they lacked ferocity, bravery, or ability, the noble virtues of the warrior. Rather, victory was stolen from them, by a lack of courage, resolve, and steadfastness of inept public officials, cowardly, self-indulgent college students, and worse, traitoress returning veterans who “betrayed” their comrades by speaking out against the war, revealing the myth, and shamelessly desecrating the warriors’ ethos by publicly discarding their war medals, the icons of mythological heroism.

Such treason and lack of patriotism, they would have us believe, are threatening our effort in Iraq today. The myth lives off the pain and suffering of war’s participants and the very mention of those who have already been injured or died discourages any talk of impropriety or wrong doing or of ending the conflict before final and ultimate victory has been achieved.

Many family members of those killed in war are also understandably hesitant to acknowledge the truth about war because the myth, they’ve been influenced to believe, helps them cope with their tragic loss. They speak of their lost loved ones as heroes and are comforted by the thought that they suffered or died for some important cause, to rectify some dire circumstance, to eradicate some prevailing evil. All that remains are the memories, letters, photos, a Purple Heart, and pride in their child’s sacrifice in behalf of freedom and American values. Dying for a mistake would, in their view, make the death more tragic and living with the loss more intolerable. Once war becomes mythological and intricately linked to the warrior, any questioning of purpose, justness or necessity dishonor those who died, discredit the sacrifices of those who served, and further overwhelms those struggling to recover from its inevitable trauma.

Many family members of those killed in war are also understandably hesitant to acknowledge the truth about war because the myth, they’ve been influenced to believe, helps them cope with their tragic loss. They speak of their lost loved ones as heroes and are comforted by the thought that they suffered or died for some important cause, to rectify some dire circumstance, to eradicate some prevailing evil. All that remains are the memories, letters, photos, a Purple Heart, and pride in their child’s sacrifice in behalf of freedom and American values. Dying for a mistake would, in their view, make the death more tragic and living with the loss more intolerable. Once war becomes mythological and intricately linked to the warrior, any questioning of purpose, justness or necessity dishonor those who died, discredit the sacrifices of those who served, and further overwhelms those struggling to recover from its inevitable trauma.

I can truly understand and sympathize with these veterans and family members whose motivation in embracing the mythology is the fear that their efforts and sacrifices or those of their loved ones would be defiled or diminished should their war be remembered as it truly was, unnecessary, unjust, and misguided. I can empathize with their apprehension as I too have wrestled with such concerns. Was it all for nothing? Did our comrades and loved ones die in vain? While such questions are certainly anxiety provoking, I have realized, however, that the cost of a false sense of comfort is unacceptably high and that we ignore the realities and lessons of past wars at our own peril. As long as we mythologize war and connive to change history, the divisiveness that surrounds Vietnam will never be resolved and the underlying and pervasive pain of war and of loss will forever linger and fester.

I can truly understand and sympathize with these veterans and family members whose motivation in embracing the mythology is the fear that their efforts and sacrifices or those of their loved ones would be defiled or diminished should their war be remembered as it truly was, unnecessary, unjust, and misguided. I can empathize with their apprehension as I too have wrestled with such concerns. Was it all for nothing? Did our comrades and loved ones die in vain? While such questions are certainly anxiety provoking, I have realized, however, that the cost of a false sense of comfort is unacceptably high and that we ignore the realities and lessons of past wars at our own peril. As long as we mythologize war and connive to change history, the divisiveness that surrounds Vietnam will never be resolved and the underlying and pervasive pain of war and of loss will forever linger and fester.

The images of the destruction of the Twin Towers and the tragic and inexcusable deaths of so many innocent persons // are profoundly troubling and will take their place beside the other traumatic experiences of devastation and slaughter that will forever haunt my existence.Over the long term, however, what threatens the very foundations and fabric of our way of life in these dangerous times is not some amorphous, enigmatic horde of bloodthirsty terrorists. Rather, it is the assault upon truth, individual freedom, and the values of justice and morality by those opportunists, obsessed and motivated by wealth and power, determined to forward their “Corporacratic” agenda. To meet this threat true patriots must recognize the perversion and garner the strength of character and presence of mind to demand truth rather than to comfort themselves with deception, to live courageously in reality // rather than cower trembling in myth and fantasy, to stand defiantly apart from the crowd rather than to find refuge within the obeisant multitude, to boldly withstand criticism and ostracization if need be rather than to wallow compliantly in a vacuous approval and acceptance, and to live principally rather than hypocritically.

The images of the destruction of the Twin Towers and the tragic and inexcusable deaths of so many innocent persons // are profoundly troubling and will take their place beside the other traumatic experiences of devastation and slaughter that will forever haunt my existence.Over the long term, however, what threatens the very foundations and fabric of our way of life in these dangerous times is not some amorphous, enigmatic horde of bloodthirsty terrorists. Rather, it is the assault upon truth, individual freedom, and the values of justice and morality by those opportunists, obsessed and motivated by wealth and power, determined to forward their “Corporacratic” agenda. To meet this threat true patriots must recognize the perversion and garner the strength of character and presence of mind to demand truth rather than to comfort themselves with deception, to live courageously in reality // rather than cower trembling in myth and fantasy, to stand defiantly apart from the crowd rather than to find refuge within the obeisant multitude, to boldly withstand criticism and ostracization if need be rather than to wallow compliantly in a vacuous approval and acceptance, and to live principally rather than hypocritically.

For Mr. Cadmus and those of us who have experienced the trauma and horror of the battlefield, or suffered the loss or injury of a loved one, accepting the truth about war, though difficult and disconcerting, will ultimately prove uplifting and curative. When we have realized the deception and the mythologizing of war, and begin to see clearly, it becomes apparent that our legacy and our dignity, self-respect, and integrity, rest not upon fantasy, lies, and fabrications. We have proved our patriotism, selflessness, valor, and nobility, not with shallow rhetoric but by our actions and our sacrifices in doing what we were deceived into believing was necessary and right. Though we as veterans must accept some personal responsibility for our actions, culpability must be shared by all who supported the war or did nothing to stop it. Most blameworthy, of course, are those political leaders, whose avarice for wealth and power, misguided policies, incompetence, and paranoia, ultimately makes killing, dying, and grieving inevitable. Unfortunately and tragically, perhaps war is a reality that will not soon go away and sacrifices on the field of battle will again be required. But by demanding truth and recognizing war as it truly is, we will ensure that it remains a means of last resort, that no other person will again have to kill, die, or grieve the loss of their son or daughter for a cause that is misguided, and, perhaps, most important, that those who dare to initiate such wars and connive to use deception and myth to encourage participation and support are held responsible for their crimes against humanity,

For Mr. Cadmus and those of us who have experienced the trauma and horror of the battlefield, or suffered the loss or injury of a loved one, accepting the truth about war, though difficult and disconcerting, will ultimately prove uplifting and curative. When we have realized the deception and the mythologizing of war, and begin to see clearly, it becomes apparent that our legacy and our dignity, self-respect, and integrity, rest not upon fantasy, lies, and fabrications. We have proved our patriotism, selflessness, valor, and nobility, not with shallow rhetoric but by our actions and our sacrifices in doing what we were deceived into believing was necessary and right. Though we as veterans must accept some personal responsibility for our actions, culpability must be shared by all who supported the war or did nothing to stop it. Most blameworthy, of course, are those political leaders, whose avarice for wealth and power, misguided policies, incompetence, and paranoia, ultimately makes killing, dying, and grieving inevitable. Unfortunately and tragically, perhaps war is a reality that will not soon go away and sacrifices on the field of battle will again be required. But by demanding truth and recognizing war as it truly is, we will ensure that it remains a means of last resort, that no other person will again have to kill, die, or grieve the loss of their son or daughter for a cause that is misguided, and, perhaps, most important, that those who dare to initiate such wars and connive to use deception and myth to encourage participation and support are held responsible for their crimes against humanity,

In times such as these, we hear endless talk of patriotism, of appreciation, and of support for the troops and for veterans. Nevertheless, within the mythology, patriotism, appreciation, and support mean, for most, especially those personally unaffected by war, boldly displaying a “We Will Never Forget” bumper sticker, flying the flag, or decorating trees with yellow ribbons, knee jerk reactions to an hysteria incited by war’s benefactors. Here is the reality. See through the myth. Is it reasonable to believe that we truly support the troops by condemning and discouraging protests against leaders and their policies that send them ill-prepared, ill-equipped, and in inadequate numbers to fight wars that are unnecessary and ill-advised? Or that we truly appreciate the sacrifices of our veterans by remaining silent when those same leaders inadequately provide for their medical, psychological, and emotional needs as they return from war bleeding, scarred, and broken? Tragically, once the frenzy of war abates, shallow feelings of patriotism soon degenerate to apathy and indifference. The rhetoric aside, whether by their action or their indifference, in truth, most regard members of the military as expendable tools of war, cannon fodder, and veterans as nuisances, frauds, malingerers, burdens on the economy, and as an uncomfortable indictment of a collective responsibility for an ill-conceived foreign policy most would rather ignore. The fact that so many of our heroic sons and daughters are languishing abandoned, their emotional and psychological injuries untreated, their needs ignored, is a national tragedy and disgrace and an inevitable consequence of a view of war that is mythological. The fact that we have become isolated in the world, respected no longer for our ideals, but, rather, feared for our brutality, no longer admired for our values of justice and freedom, but hated for our hypocrisy and intolerance, should bring a tear to the eye and anger to the heart of anyone who truly loves America. Such outrage requires, no demands, the real patriot to embrace truth and take to the streets and cry out in condemnation and protest against this corrupting and disgracing of America by those political leaders and their coconspirators who cherish not our values and way of life but only wealth and power.

In times such as these, we hear endless talk of patriotism, of appreciation, and of support for the troops and for veterans. Nevertheless, within the mythology, patriotism, appreciation, and support mean, for most, especially those personally unaffected by war, boldly displaying a “We Will Never Forget” bumper sticker, flying the flag, or decorating trees with yellow ribbons, knee jerk reactions to an hysteria incited by war’s benefactors. Here is the reality. See through the myth. Is it reasonable to believe that we truly support the troops by condemning and discouraging protests against leaders and their policies that send them ill-prepared, ill-equipped, and in inadequate numbers to fight wars that are unnecessary and ill-advised? Or that we truly appreciate the sacrifices of our veterans by remaining silent when those same leaders inadequately provide for their medical, psychological, and emotional needs as they return from war bleeding, scarred, and broken? Tragically, once the frenzy of war abates, shallow feelings of patriotism soon degenerate to apathy and indifference. The rhetoric aside, whether by their action or their indifference, in truth, most regard members of the military as expendable tools of war, cannon fodder, and veterans as nuisances, frauds, malingerers, burdens on the economy, and as an uncomfortable indictment of a collective responsibility for an ill-conceived foreign policy most would rather ignore. The fact that so many of our heroic sons and daughters are languishing abandoned, their emotional and psychological injuries untreated, their needs ignored, is a national tragedy and disgrace and an inevitable consequence of a view of war that is mythological. The fact that we have become isolated in the world, respected no longer for our ideals, but, rather, feared for our brutality, no longer admired for our values of justice and freedom, but hated for our hypocrisy and intolerance, should bring a tear to the eye and anger to the heart of anyone who truly loves America. Such outrage requires, no demands, the real patriot to embrace truth and take to the streets and cry out in condemnation and protest against this corrupting and disgracing of America by those political leaders and their coconspirators who cherish not our values and way of life but only wealth and power.

Copyright © Camillo C. Bica 2006